Matos Massei 2021

An Eye for An Eye Redux; Not All Those Who Wander Are Lost; and The Power of Words

Welcome to the 7 new people who have joined us since last Thursday! If you aren’t yet subscribed, you can join our community of 894 curious and discerning folks striving to activate their highest and best by subscribing here:

Hey friends!

Here’s the link to the printable sheet.

Here’s the link if you prefer reading this and much more on the TorahRedux website.

If you have questions or comments, or just want to say hello, you can reply to this message directly - it’s a point of pride for me to hear that my work positively impacted you, and I’ll always respond.

If you like this week’s edition of TorahRedux, why not share it with friends and family who would appreciate it?

And here’s some of what I have to say about this week’s Parsha; I hope you enjoy it, and as always, I hope you have a fabulous Shabbos.

An Eye for An Eye Redux

4 minute read

One of the most bizarre and incomprehensible laws of the entire Torah was also one of the ancient world’s most important laws - the law of retaliation, also called lex talionis:

עַיִן תַּחַת עַיִן שֵׁן תַּחַת שֵׁן יָד תַּחַת יָד רֶגֶל תַּחַת רָגֶל׃ – An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, a hand for a hand, a foot for a foot. (21:24)

The law of retaliation isn’t the Torah’s innovation; it appears in other Ancient Near Eastern law codes that predate the text of the Torah, such as the Code of Hammurabi. All the same, it appears three times in the Torah, and its words are barbaric and cruel to modern eyes, easily dismissed as unworthy of humane civilization.

People who wish to express their opposition to forgiveness, concession, and compensation, insisting on retaliation of the most brutal and painful kind, will quote “an eye for an eye” as justification, conjuring a vision of hacked limbs and gouged eyes.

This law is alien and incomprehensible to us because we lack the necessary context; we fail to recognize its contemporary importance to early human civilization.

The human desire for revenge isn’t petty and shallow. It stems from a basic instinct for fairness and self-defense that all creatures possess, and also from a deeply human place of respect and self-image. When a person is slighted, they self-righteously need to retaliate to restore balance. It makes sense.

The trouble is, balance is delicate and near impossible to restore, so far more often, people would escalate violence, and so early human societies endured endless cycles of vengeance and violence. In this ancient lawless world, revenge was a severe destabilizing force.

This is the context we are missing. In such a world, societies developed and imposed the law of retaliation as a cap and curb violence by prohibiting vigilante justice and disproportionate vengeance. An eye for an eye – that, and crucially, no more. It stops the cycle of escalation, and tempers if not neuters, the human desire for retribution. Crucially, it stops feuds from being personal matters, subordinating revenge to law and justice by inserting the law between men, a key political theory called the state monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force.

R' Jonathan Sacks observes that the same rationale underlies the Torah's requirement to establish sanctuary cities. The Torah inserts laws between the avenger and the killer, and a court must give the order. Revenge is not personal, and it is sanctioned by society.

This was familiar to the Torah’s original audience. We ought to reacquaint ourselves with this understanding – the law is not barbaric and primitive at all; it’s essential to building a society.

Even more importantly, our Sages taught that these words are not literal, and instead, the remedy for all bodily injury is monetary compensation. The Torah forecloses compensation for murder – לא תקחו כופר לנפש רוצח. The fact the Torah chooses not to for bodily injuries necessarily means compensation is allowed. And since people are of different ages, different genders, and in different trades, with discrete strengths and weaknesses; mirroring the injury isn’t a substitute at all, so paying compensation is the exclusive remedy, in a sharp application of the rule of law – there shall be only one law, equitable to all – מִשְׁפַּט אֶחָד יִהְיֶה לָכֶם.

Before dismissing this as extremely warped apologetics, the overwhelming academic consensus is that the law was never practiced as it is written. Today, we readily understand that if we suffer bodily injury, we sue the perpetrators’ insurance company, and the ancient world understood that tradeoff too.

How much money would the victim accept to forgo the satisfaction of seeing the assailant suffer the same injury? How much money would the assailant be willing to pay to keep his own eye? There is most certainly a price each would accept, and all that’s left is to negotiate the settlement figure, which is where the court can step in. Even where the law is not literally carried out, the theoretical threat provides a valuable and perhaps even necessary perspective for justice in society.

It’s vital to understand this as a microcosm for understanding the whole work of the Torah. There is a much broader point here about how we need to understand the context of the Torah to get it right, and we need the Oral Tradition to get it right as well. The text is contingent, to an extent, on the body of law that interprets and implements it.

Without one or the other, we are getting a two-dimensional look at the very best and just plain wrong at worst. If we were pure Torah literalists, we would blind and maim each other and truly believe we are doing perfect like-for-like justice! After all, what more closely approximates the cost of losing an eye than taking an eye?! Doesn’t it perfectly capture balance, precision, and proportionality elegantly? It holds before us the tantalizing possibility of getting divinely sanctioned justice exactly right!

But we’d be dead wrong. Taking an eye for an eye doesn’t fix anything; it just breaks more things.

The original purpose of the law of retaliation was to limit or even eliminate revenge by revising the underlying concept of justice. Justice was no longer obtained by personal revenge but by proportionate punishment of the offender in the form of compensation enforced by the state. While not comprehensive, perhaps this overview can help us look at something that seemed so alien, just a bit more knowingly.

There’s a valuable lesson here.

In the literal reading of lex talionis, it’s a vindictive punishment that seeks pure cold justice to mirror the victim’s pain and perhaps serve as a deterrent.

With our new understanding, compensation is not punitive at all – it’s restitutive and helps correct bad behavior. You broke something or caused someone else pain, and now you need to fix it - and you don’t have to maim yourself to make it right!

There is nothing outdated about the law of retaliation. It’s timely as ever because we all break things. We hurt others, and sometimes we hurt ourselves too. Our Sages urge us to remember that one broken thing is bad, and two broken things are worse. We can’t fix what is broken by adding more pain and hope to heal.

Taking it further, there is a wider lesson here as well.

In seeking justice for ourselves, we needn’t go overboard by crushing our enemies and hearing the lamentations of their women. We can and should protect ourselves and our assets, but we needn’t punish our adversaries mercilessly such that they never cross us again. In a negotiation, don’t squash the other side just because you can. It’s about making it right, not winning. Channeling the law of retaliation, don’t escalate. Think in terms of restitution, not retribution.

Do all you must, sure, but don’t do all you could.

Not All Those Who Wander Are Lost

3 minute read

There are parts of the Torah that we all love, with fond memories of the wonder of learning them for the first time, like the Creation story, Avraham’s first encounters with God, the Ten Plagues, and Sinai. Some parts are a little less exciting, like the Mishkan’s design-build, the laws of sacrifices, and the 42 locations in the wilderness the Jewish People visited on their journey from Egypt to the Promised Land:

אֵלֶּה מַסְעֵי בְנֵי־יִשְׂרָאֵל אֲשֶׁר יָצְאוּ מֵאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם לְצִבְאֹתָם בְּיַד־מֹשֶׁה וְאַהֲרֹן – These were the journies of the Jewish People who departed in their configurations from the land of Egypt, under the charge of Moshe and Ahron. (33:1)

It’s worth asking what the point of this is. The Torah is not a history journal; it exists to teach all people for all time. Here we are, 3000 years later, tediously reading about rest stops. Why does it matter at all?

In a sense, it’s the wrong question to ask, and it betrays the kind of thinking we are all guilty of.

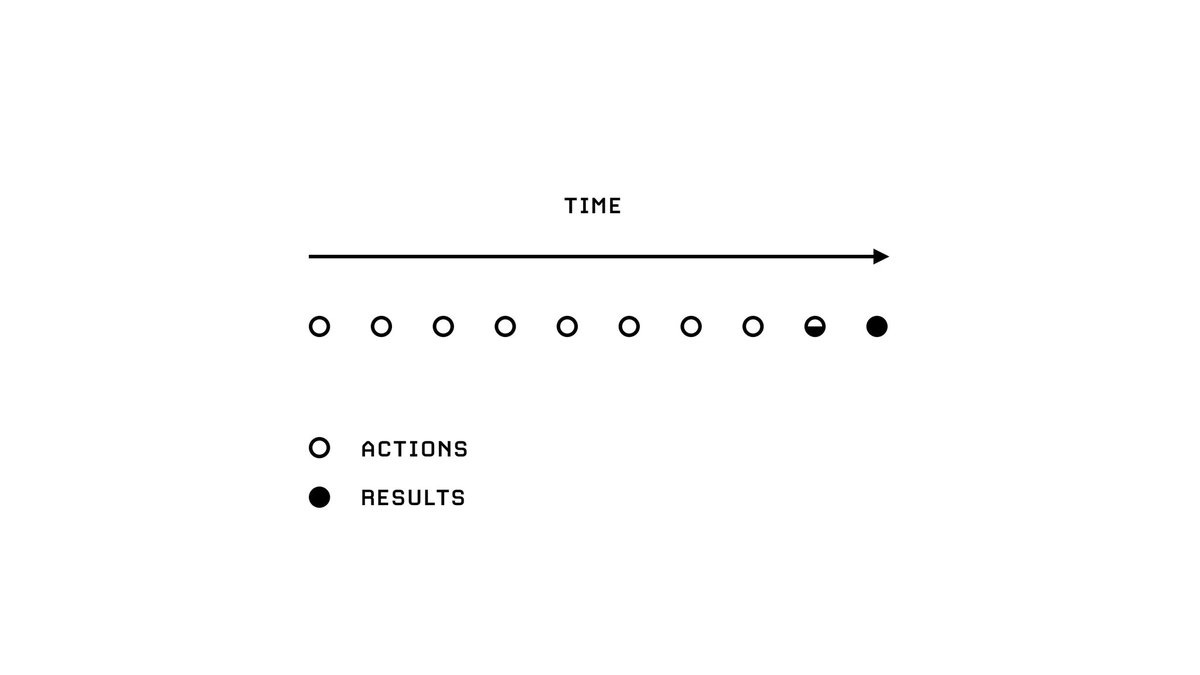

We have this expectation and perception of linear progress, consciously or not, that our lives should be a straight road, leading directly and smoothly to our destination. What’s more, we are relentlessly focussed on the outcome, where we are going. And then we get frustrated and feel sabotaged when invariably, it doesn’t pan out that way!

But this is a stiff and unrealistic view of not only progress but life itself. Progress is incremental and organic, not linear or mechanical.

If you’ve ever driven long-distance, there are a few things you just know. You can’t go straight as the crow flies, so you know you’re going to have to follow the signs that guide your way carefully to get to the right place. You know you will probably miss an exit when you’re not paying attention, and it’ll cost you 15 minutes rerouting until you are back on track. You know you will need to stop for gas and bathroom breaks. You know there will be long stretches of open road where you can cruise, and there will be times you will get stuck in traffic. You know you will have to get off the highway at some point and take some small unmarked local streets. We know this.

We trivialize the journey, and we really mustn’t. Sure, there are huge one-off watershed moments in our lives; but the moments in between matter as well – they’re not just filler! While they might not be our final glorious destination, the small wins count and stack up.

The Sfas Emes notes how the Torah highlights each step we took to put Egypt behind us – מַסְעֵי בְנֵי־יִשְׂרָאֵל אֲשֶׁר יָצְאוּ מֵאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם. We might not get where we’re going so quickly – but if Egypt is behind us, then that means we must still be moving forwards. As we get further away from our point of origin, we should keep it in the rearview mirror to orient us as a reference point to remind us that we’re headed in the right direction. However long it takes to get where we’re going, and however bumpy and curved the road is, it’s important to remember why we got started in the first place.

The 42 stops along the way were not the optimal way to get from Egypt to Israel. It doesn’t take 40 years to travel from Egypt to Israel. But it happened that way, and the Torah tells us this for 3000 years and posterity because that’s the way life is, and we can disavow ourselves of the notion that progress or life should somehow be linear. The process is not a necessary evil – it is the fundamental prerequisite to getting anywhere, even if it’s not where we expected, and it’s worth paying attention to.

We put Egypt behind us one step at a time. We get to the Promised Land one step at a time. Any step away from Egypt is a substantial achievement – even if it’s not a step in the physical direction of the Promised Land, it truly is a step towards the Promised Land.

The journey is anything but direct, and there are lots of meandering stops along the way. It might seem boring and unnecessary – I left Egypt, and I’m going to Israel! But that’s the kind of thinking we have to short circuit. It’s not a distraction – it’s our life.

Life isn’t what happens when you get there; life is every step along the way.

The Power of Words

3 minute read

Humans are the apex predator on Earth.

We share this planet with thousands and thousands of species, trillions of organisms, and none but humans carry a lasting multi-generational record of knowledge of any obvious consequence. And yet, a feral human being left alone in the woods from birth to death, kept separate and alive, wouldn’t be much more than an ape; our knowledge isn’t because humans are smart.

It’s because we speak – מְדַבֵּר.

We communicate and cooperate with others through speech, giving us a formidable advantage at forming groups, sharing information, and pooling workloads and specializations. Speech is the mechanism by which the aggregated knowledge of human culture is transmitted, actualizing our intelligence and self-awareness, transcending separate biological organisms, and becoming one informational organism. With language, we have formed societies and built civilizations; developed science and medicine, literature and philosophy.

With language, knowledge does not fade; we can learn from the experiences of others. Without learning everything from scratch, we can use an existing knowledge base built by others to learn new things and make incrementally progressive discoveries. As one writer put it, a reader lives a thousand lives before he dies; the man who never reads lives only once.

Language doesn’t just affect how we relate to each other; it affects how we relate to ourselves. We make important decisions based on thoughts and feelings influenced by words on a page or conversations with others. It has been said that with one glance at a book, you can hear the voice of another person – perhaps someone gone for millennia – speaking across the ages clearly and directly in your mind.

Considering the formidable power of communication, it follows that the Torah holds it in the highest esteem; because language is magical. Indeed, the fabric of Creation is woven with words:

וַיֹּאמֶר אֱלֹהִים, יְהִי אוֹר; וַיְהִי-אוֹר – God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light. (1:3)

R’ Jonathan Sacks notes that humans use language to create things as well. The notion of a contract or agreement is a performative utterance – things that people say to create something that wasn’t there before; a relationship of mutual commitment between people, created through speech. Whether it’s God giving us the Torah or a husband marrying his wife, relationships are fundamental to Judaism. We can only build relationships and civilizations with each other when we can make commitments through language.

Recognizing the influential hold language has over us, the Torah emphasizes an abundance of caution and heavily regulates how we use language: the laws of gossip and the metzora; and the incident where Miriam and Ahron challenged Moshe; among others. Even the Torah’s choice of words about the animals that boarded the Ark is careful and measured:

מִכֹּל הַבְּהֵמָה הַטְּהוֹרָה, תִּקַּח-לְךָ שִׁבְעָה שִׁבְעָה–אִישׁ וְאִשְׁתּוֹ; וּמִן-הַבְּהֵמָה אֲשֶׁר לֹא טְהֹרָה הִוא, שְׁנַיִם-אִישׁ וְאִשְׁתּוֹ – Of every clean creature, take seven and seven, each with their mate; and of the creatures that are not clean two, each with their mate. (7:2)

The Gemara notes that instead of using the more accurate and concise expression of “impure,” the Torah utilizes extra ink and space to articulate itself more positively – “that are not clean” – אֲשֶׁר לֹא טְהֹרָה הִוא. While possibly hyperbolic, the Lubavitcher Rebbe would refer to death as “the opposite of life”; and hospital infirmaries as “places of healing.”

The Torah cautions us of the power of speech repeatedly in more general settings:

לֹא-תֵלֵךְ רָכִיל בְּעַמֶּיךָ, לֹא תַעֲמֹד עַל-דַּם רֵעֶךָ: אֲנִי, ה – Do not allow a gossiper to mingle among the people; do not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor: I am Hashem. (19:16)

The Torah instructs us broadly not to hurt, humiliate, deceive, or cause another person any emotional distress:

וְלֹא תוֹנוּ אִישׁ אֶת-עֲמִיתוֹ, וְיָרֵאתָ מֵאֱלֹהֶיךָ: כִּי אֲנִי ה, אֱלֹהֵיכֶם – Do not wrong one another; instead, you should fear your God; for I am Hashem. (25:27)

Interestingly, both these laws end with “I am Hashem” – evoking the concept of emulating what God does; which suggests that just as God constructively uses speech to create, so must we – אֲנִי ה. The Lubavitcher Rebbe taught that as much as God creates with words, so do humans.

The Gemara teaches that verbal abuse is arguably worse than theft; you can never take back your words, whereas a thief can return the money!

The idea that language influences and impacts the world around us is the foundation of the laws of vows, which are significant enough that we open the Yom Kippur services at Kol Nidrei by addressing them.

Of course, one major caveat to harmful speech is intent. If sharing negative information has a constructive and beneficial purpose that may prevent harm or injustice, there is no prohibition, and there might even be an obligation to protect your neighbor by conveying the information – לֹא תַעֲמֹד עַל-דַּם רֵעֶךָ.

As R’ Jonathan Sacks powerfully said, no soul was ever saved by hate; no truth was ever proved by violence; no redemption was ever brought by holy war.

Rather than hurt and humiliate, let’s use our power of communication to teach, help and heal; because words and ideas can change the world. They’re the only thing that ever has.

Quote of the Week

You can’t give the world all it needs; but the world needs all you have to give.

Thought of the Week

Life can only be lived one day at a time, so of course transformation tends to occur one small step at a time. Even the most motivated and radical attempt at change is limited by the length of the day. Then, it's off to bed and back at it again tomorrow.

Impatient with actions. Patient with results.